Your cart is currently empty!

East Timor and coffee

For East Timor, one of Southeast Asia's poorest countries, coffee production is a key to sustainable development and poverty reduction.

After several hundred years under Portuguese colonial rule and several decades under Indonesian occupation rule, East Timor gained its independence in 2002.

But the country's brutal history has had major consequences, and has led to many of the challenges the country faces today. East Timor is a democracy with around 1.3 million inhabitants, the lion's share of whom live from small-scale agriculture.

The unemployment is high, the population young and the economy very vulnerable. Value creation outside the country's uncertain oil sector is small, and the country imports the majority of what it consumes. Poverty is widespread, and half of all children are so malnourished that it affects cognitive and physical development.

Coffee accounts for 90% of the country's exports outside the oil sector, and is a key factor in lifting the country's many farmers out of poverty. But the industry is underdeveloped and the income marginal. This is due, among other things, to East Timor's turbulent history.

“Up to 90 percent of coffee production was affected during the Indonesian occupation – either destroyed or ignored. What remains have in many cases been poorly maintained trees dating from the colonial era."

Susie Khamis (2015) – Timor-Leste Coffee: Marketing the "Golden Prince" in Post-Crisis Conditions

The coffee industry in East Timor

Very low income

30% of East Timor's inhabitants depend on coffee production. At the same time, income is marginal and unstable.

The average Timorese coffee farmer earned between NOK 3,000 and 5,000 in 2021.

Low production

The coffee trees are old and poorly maintained, and the productivity per hectare is almost 1/10 compared to Brazil.

Unstable production

The coffee bean is very climate sensitive, and new weather patterns affect the crops. Production in 2022 is probably halved compared to 2021 due to an abnormal rainy season.

Unstable international prices

International coffee prices vary widely - from under NOK 20 per kilo in 2019 to over NOK 40 per kilo today. How much the farmers get from this depends on local conditions, but in East Timor it varies between 20 and 30 per cent.

Despite the fact that prices have been high in the last two years, the farmer's income is still minimal. The main problem is that in the international coffee trade, farmers get an ever-smaller share of the pie.

All coffee from East Timor is natural organic, as pesticides have never been used on the island.

But since it is expensive to have production certified as organic, most coffee from East Timor is sold as conventional coffee.

We do not spend resources on certifications, but sell just as much natural coffee.

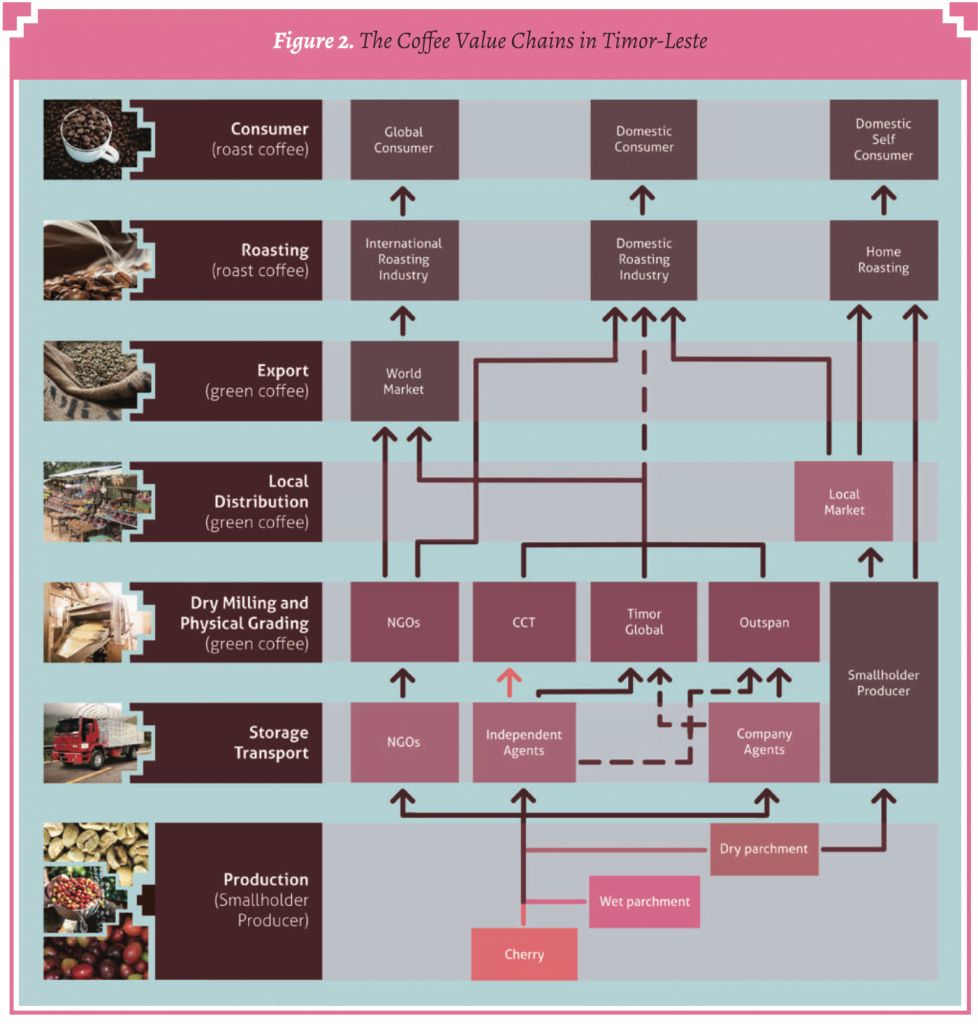

The value chain

If you buy a bag of coffee (250 grams) for NOK 50, the average Timorese farmer will get around NOK 4 of that - equivalent to 8 percent. 50 years ago, on the other hand, the proportion was around 20 per cent. Since 1990, the balance of power in the international coffee trade has largely shifted in favor of large global players, who through certifications and quality requirements "squeeze" more and more profit out of production.

In addition to large conventional players, a number of players also operate on a smaller scale, and often in "direct contact" with the producers. However, whether this improves the living conditions for the farmer is not always clear - research indicates no or small effects of such trade structures (Vicol et al., 2018; Hernandez-Aguilera et al., 2018; Neilsen, 2019). This can be due to several reasons, including a lack of social motives, local roots and local knowledge.

Konfiansa – coffee trading on the farmer's terms

As a counterweight to the majority of today's coffee industry, Konfiansa wants to create a value chain based on justice and solidarity.

Literature

Khamis, S. (2015) Timor-Leste Coffee ? Marketing the "Golden Prince" in a post-crisis condition. Food, Culture & Society. 18: 481-500

Grabs, J., Ponte, S. (2019). The evolution of power in the global coffee value chain and production network. Journal of Economic Geography, 19: 803?828.

Hernandez-Aguilera, JN, Gómez, MI, Rodewald, AD, Rueda, X., Anunu, C., Bennett, R., & van Es, HM (2018). Quality as a driver of sustainable agricultural value chains: The case of the relationship coffee model. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27, 179?198

Neilsen, J. (2019). Livelihood upgrading. In S. Ponte, G. Gereffi, G. & Raj-Reichert (Eds.), Handbook on Global Value Chains. Edward Elgar.

Talbot, JM (1997) Where does your coffee dollar go?: the division of income and surplus along the coffee commodity chain. Studies in Comparative International Development, 32: 56?91.

Timor-Leste Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (2019). National Coffee Sector Developmental Plan 2019 ? 2030. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked- documents/51396-001-sd-02.pdf

Vicol, M., J. Neilson, D. F. S. Hartatri and P. Cooper (2018). ?Upgrading for whom? Relationship coffee, value chain interventions and rural development in Indonesia?, World Development, 110, 26?37.

Interviews with Timorese farmers and players in the coffee industry conducted July 2022.