Your cart is currently empty!

The power of coffee

How does 'sustainable' coffee affect farmers? This study analyzes how farmers are affected by sustainability within the coffee industry.

My name is Bjørge Bondevik and I am one of the founders of Konfiansa. I wrote my master's thesis on the coffee industry in East Timor, and now I am working on a PhD on the topic. Read more about what I found out in my master's thesis below.

Coffee and injustice

Global coffee production emerged as a result of colonial power in tropical areas, and ever-increasing demand among European coffee houses. The pattern is the same today: all production takes place in tropical areas around the equator (that's the only place coffee can be grown), and Europeans are still the biggest drinkers. Per capita, only Finland drinks more coffee than us Norwegians!

Coffee production and poverty are strongly correlated. About half of the world's approximately 15 million small-scale coffee farmers live in poverty, and around one in four in extreme poverty. At the same time, the industry has never been more sustainable. Over half of global production is certified through various standards, including Fairtrade and the Rainforest Alliance.

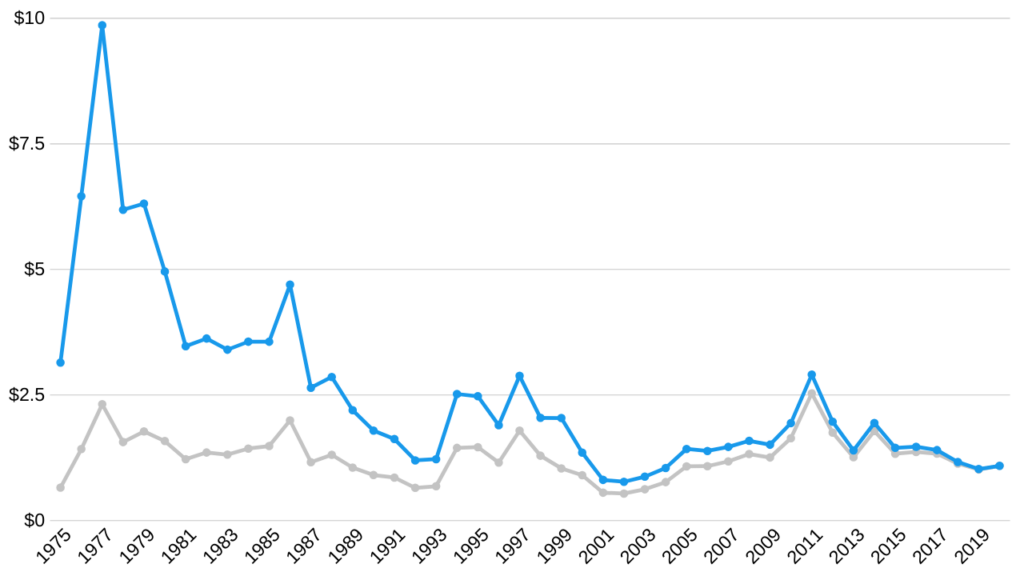

The price of coffee since 1970

The coffee price (which reflects how much the farmer gets per kilo of coffee) has been roughly stable since 1970 (grey line). Taking inflation into account, the international price of coffee has fallen sharply. In certain periods, even farmers go into the red if they produce coffee.

In 1970, the farmer received approximately 30% of the money we paid for coffee in the shop. Today, the number has fallen to 5%.

The price of coffee reflects a precarious situation for the vast majority of coffee farmers. When Fairtrade in 2023 increased the minimum price for coffee (which, relatively speaking, has fallen sharply since they started in the 1980s), they wrote:

"Despite the recent spikes in global coffee prices, coffee farmers are struggling with inflation, skyrocketing production costs, and crop loss due to the effects of climate change. Many coffee farmers are abandoning their farms in search of opportunities elsewhere and young people today in coffee-growing communities struggle to see a future in coffee. The fact that farmers cannot make a living in coffee is a tragic commentary for the industry and a huge risk for the future of the global coffee sector as a whole"

Despite this, half of global production is certified sustainable. Are certified farmers any better off than non-certified farmers? The short answer is no.

In very few cases, a certification will change the situation of a coffee farmer. A long line research studies shows that in the vast majority of cases Fairtrade does not significantly improve the lives of small-scale farmers or their families.

Coffee and East Timor

Apart from some oil production, coffee is East Timor's only export industry and a product essential in the country's further development. At the same time, the coffee industry is down with a broken back, and faces a number of challenges.

East Timorese farmers are among the world's most vulnerable and poor coffee farmers. The income is not only low - it is also very unstable and production is increasingly threatened by climate change. Malnutrition is a major problem in East Timor, and the lion's share of farmers depend on loans from local agents to survive during the year.

“The situation was even better during the occupation. Now the expenses are high and the income very low. Even those who sell at the market earn more than coffee farmers now.”

This master's thesis was written in 2023 and focused on the effect of Fairtrade and relationship coffee on farmers' living conditions. Based on interviews and statistics obtained from over 60 coffee farmers and 24 industry players, I found no significant improvements in farmers' living conditions. This despite the fact that Fairtrade and relational coffee reduce the power of local agents and ensure a shorter value chain. The potential for change is clearly greatest in relationship coffee.

What does 'sustainability' do in the coffee industry?

Does a farmer benefit from you buying Fairtrade certified coffee? Does it help to buy coffee through someone who claims it is bought 'directly from the farmer'? Almost all research indicates that the actual effect is many times lower than what the players claim.

In East Timor, the effect of coffee interventions can be summarized as follows:

- The power of local agents is lower. These agents usually have a lot of power, and take 20-40% of what the farmer earns in lieu. Relationship coffee removes this link completely, while in certified coffee the agent has been replaced by a cooperative.

- Better traceability. This means that farmers can get paid better for higher quality. In conventional coffee, there is no link between the farmer and the exporter. Quality bonuses therefore accrue to intermediaries and not to the farmer himself.

- In relationship coffee, there is also room for the farmer to express his needs. Since actors in relationship coffee depend on the farmer's loyalty, the farmer is in a position to communicate challenges and potential for improvements.

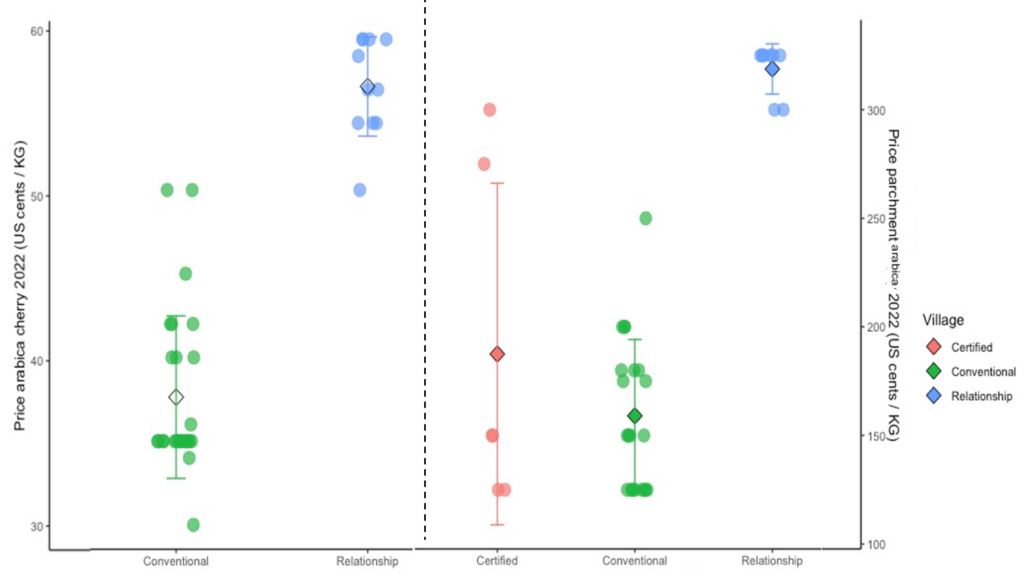

If you look only at price, the effect of relationship coffee is great. If a farmer produces high-quality coffee, he earns between 50-100% more per kilo than farmers who sell to conventional players. The price effect in certified coffee is much smaller.

For relationship coffee (blue), in 2022 the farmer received up to 60 cents/kg when he sold the whole coffee berry, compared to (in most cases) 35 cents/kg in the conventional market. When the farmer sold dried coffee (then the weight is also five times lower), relationship coffee yielded a whopping 3.25$/kg in 2022, while the price in the conventional market was around 1.75$/kg.

The price effect in certified coffee is significantly lower. At the same time, Fairtrade provides a premium of 44 cents/kg of green beans, but the lion's share of this goes to the cooperative's operational costs.

But how does it affect farmers' living conditions?

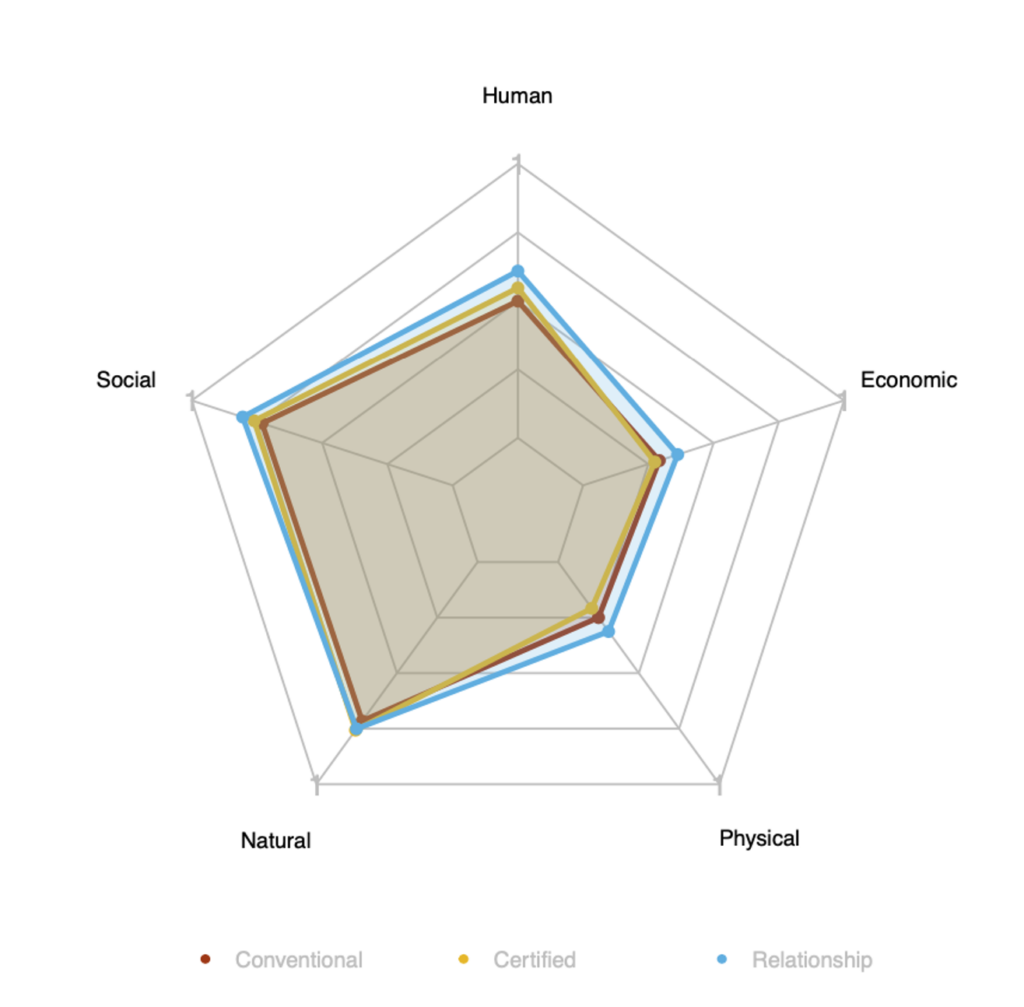

This study finds no significantly positive effects on farmers' living conditions as a result of relationship coffee/certified coffee. Divided between human, financial, social, natural and physical capital, farmers associated with relationship coffee score only marginally better. The calculation has taken into account what the individual farmer feels is important for one's own quality of life.

The reasons for this are complex. One reason is that neither relational coffee nor certified coffee gives farmers anything beyond basic knowledge about coffee ('lack of empowerment', you could say): Training programs are often very short and are mainly about improving quality (which benefits the exporter), and many value chains are completely dependent on foreign management.

In East Timor it is also the case that productivity is the main problem – not price. Per hectare, a Colombian farmer produces five times as much coffee, and a Brazilian farmer ten times as much coffee. Still, as long as production is low, better pay per kilo of coffee is of little help. Better knowledge of cultivation can more than triple productivity (also in organic production), but until now farmers associated with relationship coffee/certified coffee have not been able to increase productivity. This is also connected to the fact that if you want to increase productivity, you have to reduce production for 1-2 years, which very few farmers can afford.

Knowledge of increased productivity is also a big challenge, and one that relationship coffee/certified coffee has not been able to tackle. There are many reasons for many farmers' knowledge gaps, but the colonial (and occupation) history of the country plays an important role. At the same time that Timorese have been forcibly relocated and internally displaced (thus suddenly finding themselves in a coffee-producing area), coffee has also evolved to become part of their culture and identity. This means that many continue to produce coffee - despite the fact that they are not particularly good at it - even in situations where job opportunities outside the farm would be more economically profitable.

Sustainable interventions in the East Timorese coffee sector must therefore have a strong focus on increased productivity and better practices, but most importantly: They must make it possible for Timorese themselves to take ownership and management of the value chain.

The president of the East Timor Coffee Association (ACT) put it this way:

[How much of the low productivity is due to the colonial and occupational history?]

A lot. During the colonial time, we lacked initiative and creativity. Even if we knew something was wrong, we would still do it and say it was good. And then during the occupation, our mentality got disrupted, and we lost a lot of knowledge. And when we got independence, NGOs came and gave us money and helped us without giving us ownership. We still haven't learned. [Do you think RC interventions contribute in a positive or negative way?] I think it is good? after the independence, they ensured a market for coffee. But we need to give more power to the farmers. [What do you mean by power?] Ownership. We must prepare locals to take over and manage the structures and exports. […] We should let the locals run the business, and have their own creativity. [Do you believe some of these interventions constrain Timorese creativity?] One must make a reflection if a community can take ownership. But I think it is time, it has been 20 years already (since independence). It is not sustainable if the farmer remains dependent on these structures.

Local institutions and traditions also play a central role - often more important than coffee - for farmers' livelihoods. Local elites, moneylenders and religious authorities can in some communities, through various structures, 'capture' part of a farmer's income. Local presence is therefore a key to ensuring that increased income and support benefit the farmer. Relationship coffee has a much greater potential than certified coffee to work with local institutions and ensure that the funds go to the farmer.

While certified value chains in East Timor primarily focus on follow/accommodate the requirements from, for example, Fairtrade, relationship coffee has a greater focus on develop local community. If this is to lead to an improvement in farmers' living conditions, however, it requires an increased focus on increased productivity, local institutions and a commitment to educating people and understanding the challenges they face. The structural challenges in rural East Timor are so great that an exclusively focus on better quality contributes little to sustainable development.

Disclaimer: This is a master's thesis project. Due to limited resources, only 62 farmers and 24 industry actors were interviewed. This is only a snapshot study, and there are many potential sources of error in the conclusions. All photos are taken by the author.

Download the entire assignment here: